Tuesday, August 01, 2006

n is here . It's August and if its hot where you are, we have a partial cure. Scroll down to "Foxhunt, French Horn, and Mozart". A foxhunt snowscene joins together with a Mozart Horn Concerto to make a snow-cone of a video. Lots of Rollicking-Frollicking 6/8. Next comes a study of Henrietta Johnston, early colonial portraitist, followed by a small salute to Correggio and one of his wonderful frescos. Don't as me why that funny underline is there. That darn line has been following me around all day. It must have some subtle significance.

n is here . It's August and if its hot where you are, we have a partial cure. Scroll down to "Foxhunt, French Horn, and Mozart". A foxhunt snowscene joins together with a Mozart Horn Concerto to make a snow-cone of a video. Lots of Rollicking-Frollicking 6/8. Next comes a study of Henrietta Johnston, early colonial portraitist, followed by a small salute to Correggio and one of his wonderful frescos. Don't as me why that funny underline is there. That darn line has been following me around all day. It must have some subtle significance.Anyone traveling to

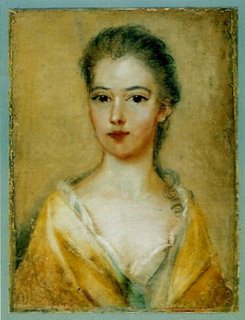

Henrietta Johnston painted wonderful portraits. All of them were oil pastels or crayons as they are often called. Crayons were a new medium during Henrietta’s time (c. 1674-1729) and during that era, the new medium was enjoying some of its most perfect realization. Jean Baptiste Chardin was working with it in

Henrietta’s pastels are not standard pastel renderings, but are portraits with soul and style, grace and mystery. When I viewed one for the first time, I was struck by its softness and impressionistic quality. Of course, the images are not Impressionistic at all. They are exciting in similar ways, however. The details are suggested rather than specified. The portraits are refined by their warmth and expressiveness rather than by scrupulous attention to “photographic” exactitude – as if photographs looked ‘real” most of the time. Her colors are blended with an eye for overall effect, at once subtle and bold.

Henrietta took liberties, too. For example, most sets of the subject’s eyes, in her works, are larger than life. There is a temptation among some portrait artists to render the eyes overly large for the reason that the viewer will be attracted to the painting. When seen at an angle across a large room, the eyes may seem livelier, in this way. Unfortunately, when the viewer is directly in front of the painting, the eyes seem uncomfortably large and tend to overpower the whole image. Nonetheless, Henrietta’s works remain a complete delight and her subjects eyes have been called liquid and poignant.

The life of Henrietta Johnston could be made into one of those children’s books that inspire kids to be strong and resourceful. Her maiden name was Henrietta de Beaulieu. She was born in

By the time Henrietta was twenty, she married a Mr. Robert Dering. After the ceremony in Saint Martin in the Fields, the couple was off to

Robert Dering died young, leaving Henrietta a widow, after approximately four years of marriage. There were also two daughters born to the couple. One was named Mary and there was another whose name did not come down in official records. The solidarity of the Dering family, coupled with Henrietta’s portrait sales, provided necessary support. In a few years, Henrietta met Gideon Johnston, a cleric in the Anglican Church, and a widower with two sons. They would be married in 1705 and her life would begin a dynamic new chapter.

The Johnstons, along with Henrietta’s two daughters and Gideon’s two sons, moved back to London, briefly, then they were off to Charles Town, (aka Charleston) South Carolina. Why would anyone move to

Henrietta made a trip to

Gideon, who struggled seriously all his life for the good of the Anglican Faith, died as the result of accidental drowning in 1716. Henrietta’s French qualities probably helped her survive. She had a simpatico with beauty and style, coupled with a skill for practical matters. She lived until 1729 and made an indelible mark on

Henrietta blended a life of service and struggle with a superior talent for art. If she had lived in a different time and been able to receive better material care, perhaps we would have seen a more varied collection of her work. We have no florals or landscapes that have yet surfaced. Nevertheless, portrait artists were a dime I dozen in the era before photography, but few of them achieved the distinctive style and loveliness, which is the hallmark of Henrietta Johnston’s work.

One last bit is for the residents of

Henrietta Johnston, Mrs Samuel Prioleau

Henrietta Johnston, Mrs Samuel Prioleau Henrietta Johnston, Colonel Sam Prioleau

Henrietta Johnston, Colonel Sam Prioleau

Henrietta Johnston, Henriette Charlotte de Chastaigner

Henrietta Johnston, Mary Dubose

Henrietta Johnston, Irish Girl

Henrietta Johnston, Irish Girl

Here is a fine fresco from Correggio. He seemed to have the knack for facial expressions and rendered the subject at some exquisite moment in time. In this case, the combination of the Madonna's demure and the child's possessive, knowing look combines to engage us in the delight of the mother and baby. It reminds us of the strength and gentility of such golden moments, and how they are worth trying to remember and respect. That is why we love this painting.

Here is a fine fresco from Correggio. He seemed to have the knack for facial expressions and rendered the subject at some exquisite moment in time. In this case, the combination of the Madonna's demure and the child's possessive, knowing look combines to engage us in the delight of the mother and baby. It reminds us of the strength and gentility of such golden moments, and how they are worth trying to remember and respect. That is why we love this painting.